In AMC Network’s new retro TV series “Halt and Catch Fire” we meet the anti-hero protagonist, Joe McMillan, who is struggling to design and launch a new PC during the dawn of the PC revolution in the early ‘80’s. Other characters argue that their little company “Cardiff Electric” has no business in the PC market. They are a Texas software company with no experience designing or building hardware, and no credibility in the market. They pose the very reasonable question, ‘Why would anyone buy from us?’

Joe, a former IBM salesman turned PC “visionary” realizes that the PC market is still in its infancy and that anyone can still become the market leader in this still “Blue Ocean” market (although that terminology was not yet in use during the time period of this story).

In answer to the question “why us?” he goes to the whiteboard and writes a simple but powerful two line value proposition:

2x Fast

½ Price

It is a dramatic moment that seems to fizzle as Gordon the Engineer points out that it simply isn’t possible to create a computer two times faster than an IBM PC and sell it for half the price, because the laws of physics (combined with the laws of economics) prevent it.

Joe is undaunted. He believes that Gordon and his engineering team can solve the technical challenge that the market leader IBM, couldn’t or wouldn’t even try to solve. To make Joe’s vision a reality the team will have to make numerous technological advancements that seem unlikely for a small company with limited time and resources. Gordon shakes his head in disbelief but sits down muttering “…maybe we could crank-up the crystal…or attack it with software…” In spite of his misgivings, we can see that Gordon is hooked, and will rise to the challenge as best he can.

At twice the speed and half the cost, the Cardiff PC would offer customers 4X the value of the IBM PC. Joe believes that the Cardiff PC would completely dominate the market.

Is he right?

Although not detailed in the story line, with some reasonable speculation we can reverse-engineer what Joe is thinking as it would be described in the Quantitative Product Market Fit framework.

Let’s first assume that Joe is right that “Speed” is in fact the dominant value dimension. Note that at that time the state of the art in the PC market (Apple notwithstanding) was Intel’s 8088 chip and a blinking DOS prompt. Most users predominately used WordPerfect® which didn’t need a lot of processing power, but power users were developing their own spreadsheets in Lotus 123®. In those days updating a “large” spreadsheet or graph meant having to take a 5 minute “coffee break” every few minutes while the machine was recalculating. The productivity gains from a faster machine that could reduce the wait time would be highly attractive for power users and would more than justify a higher price.

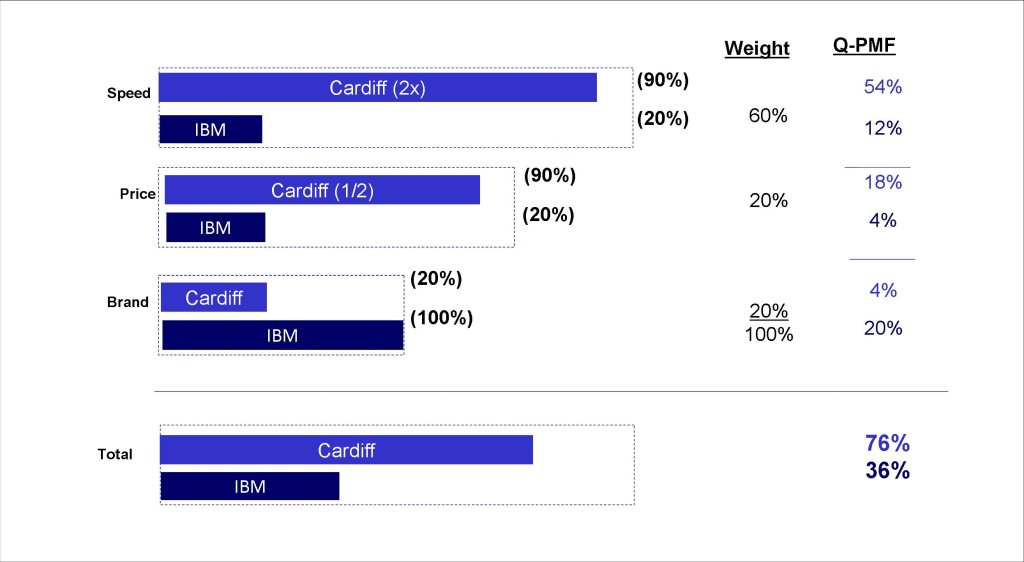

Let’s speculate that in Joe’s mind the primary value dimensions and importance weights of his primary target segment (business PC buyers) are Speed (60%), Price (20%), and Brand (20%).

Joe’s Q-PMF chart of Cardiff vs. IBM would look something like this:

In comparison the “old” IBM PC would now be noticeably and painfully slow. Let’s assume that the customer satisfaction level for Speed would fall to 20%, once people saw what they were missing. Cardiff would have a commanding Delta-Value advantage in the most important value dimension.

In a typical innovation scenario, higher performance comes at a higher cost. This would allow IBM to offset the liability of being slower by making up customer satisfaction in the price dimension. Faced with a faster but more expensive rival, IBM could make their PC a “better deal” (either by making it less expensive or by adding other valuable features or services). This would effectively split the market into two natural segments (ordinary users and power users). IBM could cede the smaller, higher priced power user market to Cardiff, but retain the larger ordinary user segment for themselves.

But Joe has already beaten them to the punch by envisioning a machine that is not only faster but also has such a low price, that IBM couldn’t or wouldn’t be able to match it.

At half the cost of an IBM PC the fictional Cardiff PC would enjoy tremendous customer satisfaction in the Price dimension, perhaps as high as 90%. (You might ask ‘why not 100%?’ The answer is because when it comes to Price, customers almost always want to pay a little bit less).

However competitive strategy is never static. One must assume that IBM would launch a counter-strategy to mitigate the imminent loss of market share. Perhaps they would add new value dimensions on which Cardiff could not compete such as special financing, better service contracts, training, or software bundles. The net result might be that IBM could salvage 20% satisfaction in the Price value dimension from the IBM loyalists.

This is not far from IBM’s actual history. IBM had a reputation of selling adequate products and services but charging premium prices. They relied on the power of their brand equity and the perhaps the self generated whispered adage that “No one ever got fired buying IBM.” This allowed them to effectively introduce a new (unadvertised) value dimension of “Job Security” which for many corporate buyers trumped most of the other dimensions and on which no other company could effectively compete.

This brings us to the Brand value dimension. IBM has an unassailable brand; Cardiff has no brand recognition at all. This is David vs. Goliath but without the sling shot. We can assume that PC buyers would be 100% satisfied buying the IBM brand.

Since Cardiff has zero brand equity should we assume that they would also have zero performance in the Brand dimension? Thankfully, no. The Early Adopter segments of most markets are the scouts who are always on the lookout for something new. Having no brand equity is not a significant deterrent to them; they will do the research on the company, trial the products, gather user feedback and form an early opinion that will influence the rest of the later market segments.

We can imagine that if Joe is successful in launching his dream machine that in later episodes BYTE magazine will write a glowing article about the blisteringly fast, and incredibly cheap new PC from a company that no one has ever heard of before. Assuming the product works as advertised (although with a title like “Halt and Catch Fire” this assumption is in doubt) they will gain positive exposure and they will eventually build meaningful brand equity. Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt and assume that they can achieve 20% satisfaction in the Brand dimension fairly quickly.

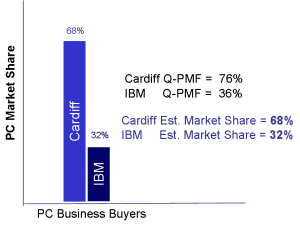

Now how does David look compared to Goliath? Cardiff has an overall Q-PMF score of 76% which is slightly better than twice IBM’s score of only 36%. Using these Q-PMF scores we can calculate what percentage of total value each brand contributes to the market and make a rough estimate of how much market share each brand should capture over time.

Our Q-PMF model suggests that Cardiff could capture 68% of the market away from IBM assuming that PC buyers are fairly homogenous and conform to our speculative Customer Value Model.

This 70/30 estimate intuitively “feels” about right. Some might ask why would we expect IBM to be able to retain any market share at all, if their product was both so inferior and over priced?

In a perfectly “efficient” market where the only value dimensions are Price and Speed, we would expect IBM’s market share to go to zero very quickly. But most markets are in fact far from efficient, even the financial markets are only mostly efficient.

Markets are made up of people who each have their own unique customer value model, and a unique ability to acquire and process new information. Some people react quickly, others don’t; and as President Kennedy once said “there is always the 7% who never get the message.”

Most people do in fact get the message, but some just don’t care that much which is a function of the long tail nature of the distribution of people’s Customer Value Models. Usually the majority of Customer Value Models tend to line up along preference lines that create clearly differentiated value segments, but some don’t. Some people have preference portfolios which are unlike the major segments.

For example this can be clearly seen in US politics where the majority of people tend to identify themselves either moderately or strongly with one of the major political parties, either the Republicans or the Democrats. But a minority of people identify themselves as “Independents” because neither of the two major parties offer a good fit with their political preferences. So even if the proposed Cardiff PC could bend the laws of physics and economics to be both faster and cheaper, there will still be some people who are not satisfied with those two dimensions and will want something else. Perhaps this explains the survival of Apple Computers.

In Halt and Catch Fire there is no doubt that Joe’s vision is correct, the only question is can a rag-tag band of misfits accomplish what the market leader can’t? And that is what will keep people watching.